Filed under: art, interview | Tags: $$$, academy, art, ethics, genius, poverty, starving artist, writing

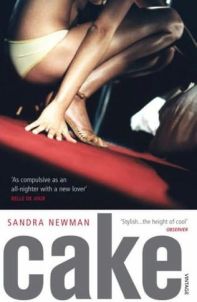

Sandra Newman is the author of the novels Cake and The Only Good Thing Anyone Has Ever Done; as well as the book How Not to Write a Novel (co-written with Howard Mittelmark); and has published short fictions in numerous venues, notably in Conjunctions (<–read “The Potato Messiah”). She was interviewed in MP#3 about Cake, bank robbery, and gender and experimental writing.

Here’s what she had to say about the writing life and $$ woes. (Interview conducted by Leeyanne Moore.)

When you use the term “starving artist” in relation to yourself, how literal are we talking in terms of actual starving? What would you count as part of the territory that comes with being a “starving artist” and what would you disallow?

I haven’t ever been starving in the food sense; in my experience, in the Western world, the only way one could arrive at “starving” would be via ”utterly friendless.” And while my adventures in nearly starving have put a strain on my relationships sometimes (I don’t often borrow money, but I do stay on people’s couches for prolonged periods of time in my recurring dry spells), this has never gone into friendless territory. People with non-art jobs have all the food in the world, in my experience. In fact, you can pretty much make a three-course meal in the kitchen of a gainfully employed person without them ever knowing that the food is gone.

For me, most of being a starving artist in America is about taking risks that other people aren’t willing to take, sacrificing status, and often — the part no one ever talks about — making selfish decisions about other people’s welfare. Any starving artist with parents is at the very least making those parents miserable. In the vast majority of cases, s/he is also spending those parents’ money, which the parents perhaps had plans for and wished to spend themselves. Finally, any starving artist with children is going to feel like a criminal at certain points. There is no point pretending that the children would not have a better prospect in life if you worked for a reinsurance company and could afford to send them to private school. The children will be paying for your art career for the rest of their lives, in many cases. Of course, there’s no guarantee that you would have been a great success in your other, purely imaginary, business — no doubt you would just have become a starving, untalented claims adjuster. This point, however, tends not to impress anyone — people will generally relate to the artist as if she could have become a millionaire in any other field at all, at will.

What’s been your most profound moment as a starving artist in terms of suffering? Has this shaped how you view your art or how you view the world & humanity?

For me, the worst part of being a starving artist is (as alluded to above) that one cannot afford to be ethical. This is a common feature of any poverty: Brecht writes a lot about this. In the modern world, this is usually a fairly harmless thing, amounting to a sin of omission generally. You can go a long time without confronting this, but eventually there will come a time when the choice is between doing the right thing and, for instance, getting your book finished. So you end up finishing the book, even though it means living off your partner for a few months, for instance, and you know the partner has no belief that your book will sell, and in fact, your partner thinks you should get a job in insurance, because this artist crap is going nowhere. Soon the partner is gone, sans a fair chunk of money, and the book is left behind as a monument to your warped priorities.

What has been your most profound moment as an artist in terms of what you would consider success?

As far as success goes, I’ve managed to live off of literary writing for some periods — two years was the longest to date. I’ve had good reviews in major newspapers and so on, and I get to be treated like a going concern as a literary writer nowadays. People in publishing have generally heard of me. In short, I have all the success you can have as an artist without becoming famous. It would perhaps help if I were part of a clique or movement of some kind, but I turned out not to be that kind of person.

How much pride do you take in being a starving artist? Ultimately, do you think it’s worth it?

For me, being a starving artist is one of the necessary results of being an artist. Although it’s possible to succeed as an artist, of course, when we set out to be artists, we don’t know for certain whether that decision will take us into starvation, though we can make some predictions based on probability. (Making predictions based on our own estimates of our genius is another story, part of the ancient Story of the Idiot.) In reality, not many artists ever make money. People who decide that making money takes first place usually end up making some variety of near-art. I’m now in my forties, at an age when one realizes that most likely (again probability) even if I have some success in my lifetime, after I am dead it will all be completely forgotten, so my low-wage job is not necessarily more meaningful in terms of society’s needs than anyone else’s.

So, I am not proud of it at all; I try not to be ashamed of it. However, it’s what an artist is, so there’s nothing to be done about it. Artists don’t generate wealth, for the most part, but for some evolutionary reason (we guess this is to blame, anyway) we keep on being born. Hopefully this is necessary.

As a starving artist, do you enjoy NOT being part of mainstream America? Do you restrict your American cultural consumption calories, and if so how?

I don’t know about enjoying not being part of mainstream America. To me, unfortunately, mainstreamAmerica is terrifying. I don’t have to restrict my cultural calories — I have no interest in American mainstream culture at all, and I only engage in it at all because you have to, socially. I hate every second of it. I have no understanding of why people watch Hollywood movies or tv willingly, why they read glossy magazines, why they are interested in restaurant meals and fashion. It makes no sense to me at all.

I wish I felt differently, because it complicates my life. I don’t want to live in a restricted world of people who all agree with me, so in fact I spend almost all my time around people who talk about tv shows as if they have significance (once and for all, I have studied this in depth, and they don’t, not one of them does, they all don’t) and who cannot discuss Barack Obama without getting sidetracked onto Michelle’s most recent dress. Something about this is supposed to be fun. As far as I can tell, fun in this culture is defined as anything empty, dull, and tending to concentrate on the least noble aspects of humanity. It also has to be a repetition of something already long familiar to the fun-lover. But I could go on and on. The whole phenomenon beats me, though clearly it somehow is making all these other people happy.

Being around people who ignore this type of culture does make me feel better. But I can’t say that they seem any smarter or more alive or in any way superior to the people who are immersed in it. This is also mystifying to me. But it does make me feel better. For a long time, I never spoke to people who were at all mainstream, and I assumed that decades of media must have turned them into vegetables, because even five minutes of media makes me feel like I’m being turned into a vegetable. But not so. Mystifying.

Is there anything else you’d like to say about your journey, or your future, specifically to other starving artists out there?

Just a note about starving artists and the academy. It has long been the case that young people who set out to be writers are actually (and they know this) setting out to someday teach in MFA programs. Even very successful writers often have a tenured post at some university. This isn’t the end of the world, clearly, and any system which gives artists time to work while paying their bills has a lot to be said for it. At most universities, you can espouse any crazy belief without fear of reprisal. Also, you can make art that no one understands or likes for years at a time, and still survive. So, it’s a great system in many ways; the only down side is that it’s hard enough for writers and artists to know anything about life outside of the narrow world of artists and writers. We spend most of our time alone, conjuring things out of our own heads. If we spend our social time in a university setting, we run the risk of absolutely not knowing what we’re talking about. The result will be (is) a lot of books that are either about love relationships and families, with no social context of any substance, or “topical” books that get their information about society from the New York Times. (I offer you for free this reason to disdain Philip Roth.) The most popular exemplars of the latter genre are often a tissue of scare stories and urban legends, mingled with pat explanations familiar to anyone who skims the editorial pages.

There is always a place for both books about relationship woes and for books that take a safe route through predictable Problems of the Day (as there is a place for New York Times editorials). I think that young artists should be thinking about exploring the worlds outside of art and the academy, though, if they can. Meeting people from those worlds at parties is really not going to take the place of walking a mile in their shoes. I recently read something by someone who had gone as a war correspondent to the Congo where he says that a lot of people came to the Congo just to test themselves against the war. Then, more startlingly, he goes on to say “I learned that there was nothing wrong with that.” I thought that was very insightful, because it goes against our preconceptions about what can be authentic. It would be nice if people did more things in this world just to see what they were like, or to test themselves — i.e. to see what they are like.

2 Comments so far

Leave a comment

Great interview! Thanks for a very clear and reasonable articulation of one of the problems with the literary industrial complex. Also, I’m always happy to have a new reason to disdain Philip Roth.

Comment by Andrea Lawlor January 5, 2010 @ 2:14 pmI love what Sandra has to say about literary nutriment outside of the academy, how one shackles oneself to certain topics when submerged in academia. I’ve given a great deal of thought to this dilemma–how the university cradles the artist, but also cradles in the negative sense. I have How Not to Write a Novel on my shelf, but I haven’t read any of Sandra’s fiction and now will seek it out. Thanks.

Comment by Tim Horvath January 9, 2010 @ 2:14 am